Washington's new model of foreign aid for economic growth

Everybody makes money, but nobody actually makes anything.

Summary: the U.S. and the World Bank are putting more and more foreign aid money into private sector deals: for-profit investments designed to stimulate economic growth. But most of that money gets absorbed by banks in the BRICs, very little goes to poorer countries, and almost none of it to manufacturing or exports. As this style of foreign aid grows, the focus on industrialization is declining. If development finance institutions are serious about economic growth, they need to rediscover export discipline.

Since Donald Trump returned to Washington, the hottest trend in foreign aid is making deals. USAID’s model of doling out free HIV drugs and emergency food relief to poor countries has been DOGE’d. Meanwhile, Congress is set to grant new authorities to the U.S. Development Finance Corporation (DFC), which directs foreign aid to companies, especially American companies, looking to turn a profit overseas.

A block down the road from the White House, the World Bank – eager to stay in the good graces of the new administration – has doubled down on a similar strategy. Five years ago the bank's private-sector divisions (IFC and MIGA) did about $14 billion in new business, comprising about a fourth of the bank's portfolio. Last year that number hit $40 billion, and at the current pace, private sector investments will eclipse the World Bank's traditional sovereign lending portfolio in a few years time.

The result of all this is an interesting hybrid of foreign aid and industrial policy, combined with a Wall Street-style compulsion to make money and "do deals."

In theory, that's not all bad. Poor countries need to grow, and for that they need investment. If rich countries are embracing industrial policy at home – with subsidies for chosen firms, and public money taking equity stakes in private companies – why shouldn't foreign aid do the same for poor countries?

The problem is that the money is not being used to industrialize poor countries. Both the verb and the object in that last phrase are wrong. Instead, it's being invested in the banking sectors of places like Mexico and Turkey, i.e., financial intermediation for the domestic service sector (not industrialization) in middle-income BRICs countries (rather than the poorest countries in need of jobs). The result is industrial policy without any industry, and foreign aid with surprisingly few poor people involved.

Historically, poor countries have grown rich by exporting labor-intensive manufactures

From the 1950s through the 1980s several East Asian economies – South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, and the city-states of Hong Kong and Singapore – achieved unprecedented economic growth rates on the back of export-oriented manufacturing. In the decades that followed, China repeated their feat on a monumental scale.

These economies didn’t just export manufactures. As Joe Studwell documents in his bestseller “How Asia Works”, these "Asian Tigers" structured their financial systems to direct cheap capital to firms that successfully exported. This model of carefully targeted subsidies – designed to prioritize making stuff, not real estate booms and financial bubbles – stands in stark contrast to the scattershot approach taken by Washington today.

So what is it about manufacturing, specifically, that made it central to the East Asian growth experience – not to mention almost every major development success story from the British Industrial Revolution to Bangladesh’s 21st century boom?

Let’s look at three elements that distinguish manufacturing, and then later we can judge the World Bank's current IFC private-sector portfolio on these same metrics:

- Labor intensity (which I'll define as workers employed per million dollars of output, L/Y)

- Tradability (defined as the value of exports as a share of output, X/Y)

- Productivity growth (the historical rate of growth in value added per worker, Δln(VA/L))

While it’s a bit dated and doesn’t cover today’s poorest countries, the World Input-Output Database (WIOD) provides data to estimate each of these dimensions at the sector level for some larger middle-income countries, essentially BRICs+: Brazil, Russia, India, China, Indonesia, and Mexico. (Here I’m collapsing data from ISIC Rev. 4 industries to the 9 sectors listed in the IFC data for comparability).

In terms of job creation, “agribusiness and forestry” is the most labor intensive sector in the WIOD data, employing about 380 people per $1 million of output, while finance is the least labor intensive, at 31 workers per $1 million. Manufacturing is sort of middle-of-the road here at 61 workers.

Where manufacturing really stands out is on the other two dimensions: historical growth in labor productivity and export orientation. The sector that performs the worst on all these metrics is the sector where the IFC devotes the largest share of its investment: finance.

Compare that to where the World Bank puts its private sector investments

Let's start with a positive example that bucks the overall trend here: the exception that proves the rule.

In 2024, the World Bank’s private sector arm, the International Finance Corporation or IFC, made a $15 million loan to Star Garments, an American-owned, Sri Lanka-based garment manufacturing company to open up a new “cut-make-trim” factory outside Lomé, Togo.

Lots of economist would tell you that that kind of export-oriented manufacturing is, historically, the best way for poor countries to graduate up to higher levels of development. Star Garments is private-sector development finance done right: Togo is a low-income country, garment manufacturing is highly labor intensive, and the factory will export products to high-income markets.

The problem with the IFC investment in Star Garments is not that it has any secret flaw, it's that it is almost literally one of a kind: one of only a handful of cases globally of an IFC investment in export-oriented manufacturing in a low-income country in the last five years: $15 million out of a portfolio of hundreds of billions of dollars.

The problem is two-fold:

- Geographic: Development finance institutions like IFC and DFC make very few investments in the places that really need subsidized capital, i.e., low-income countries. So the reallocation of aid money from traditional public sector projects to "blended finance", private-sector oriented models means a reallocation away from poorer countries toward wealthier, faster-growing emerging markets.

- Sectoral: In the quest for financial returns, these institutions also focus heavily on financial sector development, neglecting investments in the real economy that will be necessary for economic growth.

While there are some older counter-examples –a slaughterhouse in Ethiopia in 2019, a mango plantation in Malawi in 2014, some cashew processing plants in Guinea and Mozambique from the 1990s – these are rare exceptions in an overall portfolio heavily weighted toward banking.

Over time, development finance is focusing less and less on jobs, growth, and exports

I'll continue to focus on the World Bank's IFC here, because it's the big player, but the same exercise could be done for the US DFC or the UK's BII.

To calculate the labor intensity, growth orientation, and export propensity of the IFC portfolio I take the allocation of IFC investments across sectors and combine that data with the sector statistics above from the average BRICs+ country. Imagine the two charts above as matrices. In the first matrix, the rows are industries (j=1…J), the columns are countries (k=1…K), and the values are dollar amounts. In the second matrix the rows are again industries, but the columns show industry characteristics (l=1…L) like labor intensity. If we multiply those two matrices together, we get a JxL matrix describing the implied labor intensity, growth orientation, and export propensity of the IFC’s portfolio in each country. We can do the same thing with time periods instead of countries, and repeat the exercise each year.

The pattern that emerges is disconcerting.

Over the last 20 years, from 1996 to 2025, what we see is a remarkable decline in what I’d argue is the developmental- or structural transformation-focus of the IFC portfolio. The implied labor intensity of IFC investments has declined from about 92 workers per $1 million in output in 1996 to about 72 in 2025. Whereas the IFC used to invest in sectors that had historically grown at nearly 6% per annum in the BRICs benchmark countries, that figure has fallen to nearly 3% annual growth – and an almost identical trend is observed for the ratio of exports to output in the sectors IFC chooses.

As the IFC portfolio has grown – and it has grown dramatically over the past five years – any focus on labor intensive, export oriented, fast-growing sectors has not really kept up.

So far this statement is based on implied performance, applying BRICs+ parameters to the IFC portfolio. As an alternative, I also construct a direct measure of export performance for the IFC portfolio by scraping the IFC disclosures on the web for any mention of exporting (and then humanly checking a sample, weighted toward the larger projects).

The picture confirms how unique the Star Garments story is: manufacturing projects mentioning exports are a small, and declining share of the overall portfolio. If you restrict the sample to low-income countries, in many years there are zero investments in manufacturing, and other times one or two. Never mind manufacturing much less exporting: low-income country projects as a whole remain pitifully small compared to IFC’s overall booming portfolio.

Admittedly, things look a little better for lower-middle income countries, where manufacturing investments reached about $1.6 billion in 2024, of which about $700 million were in export-oriented firms – though these were largely in low-value added industries like cement and fertilizer with exports to regional rather than international markets.

Don't banks create jobs too?

Skeptical readers who are still reading at this stage are perhaps mentally screaming that all of these numbers miss the point. The IFC doesn’t lend to banks to create more jobs as bank tellers. The goal is often very explicitly to enable local banks to lend more to the small- and medium-enterprise sector.

This is reasonable on one level: the IFC probably shouldn’t be directly involved in the retail banking business, making micro loans to SMEs in Tanzania from its headquarters in Washington. But without denigrating this good-faith effort at local economic development, it does leave open two questions.

First, there is a question of additionality and impact, even on the metrics IFC has chosen for itself. Is cheap capital for a few Mexican banks actually lowering interest rates and expanding credit access for Mexican SMEs? Or is that money getting swallowed up by bank profits? There’s very rarely any evidence provided to answer that kind of question: IFC doesn’t routinely do impact evaluation of the sort other development actors do.

The World Bank's own Independent Evaluation Group has repeatedly bemoaned this failure to demonstrate that "blended finance" – i.e., this model of lending to banks, to lend on to specific target groups like SMEs or women-owned businesses – has any development impact (see reports in 2019, 2021, and 2024), leading to some grumbling from the bank's board. A recent review of the academic literature on the topic noted, "evidence on the impact of these public programs intermediated via commercial banks is limited and rarely extends to estimates of the impact on final beneficiaries."

Second, from a development strategy or industrial policy point of view, small is not beautiful. More prosaically, it’s unclear that SME credit is the path to growth and structural transformation for the middle-income countries which are the IFC’s main clients. There is a large literature documenting the positive relationship between firm size and exporting. In many developing countries, the SME sector is a low-productivity, low-earnings job of last resort. If the IFC’s clients want to pursue outward-oriented industrialization, they’re going to need some big firms with the wherewithal to navigate international markets. Alas, IFC is not financing that kind of project.

What's the constraint? Profit incentives or a missing pipeline of projects

Earlier this year I attended a Chatham House discussion sponsored by British International Investment (BII) with people from various development finance institutions. Per the "Chatham House rule" I can't quote anybody in particular. But the entire premise of the discussion was that the supply of development finance can't find enough demand. This is often referred to as the missing "pipeline" of bankable projects in poor countries.

It is odd to hear people whose job is to give away cheap money complaining that nobody wants it, but the complaint is sincere. Many officials at the IFC, BII, or the U.S. DFC would jump at the chance to back an export-oriented manufacturing venture in (low income) Mozambique or even (lower-middle income) Tanzania.

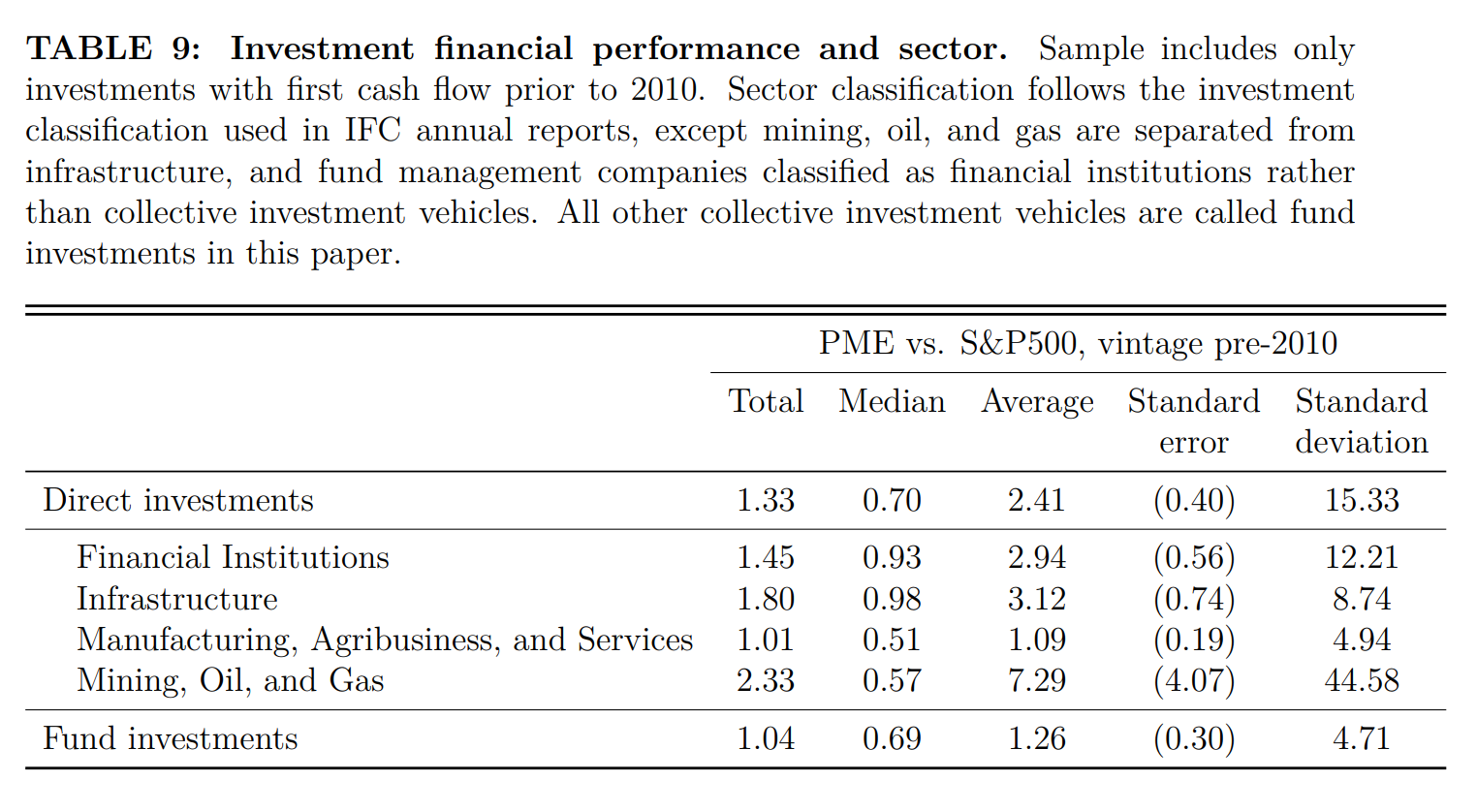

This is where profit incentives, for development finance institutions as a whole and for the investment officers within them, militates against long-run development strategy. A recent paper by Sean Cole, Martin Melecky, Florian Mölders and Tristan Reed draws on confidential IFC data to calculate the commercial return to its investments over multiple decades. They find that even after adjusting for implicit management fees, “over the long run the IFC’s portfolio of emerging market private equity has done about as well as the S&P 500 index.” But they also show significant differences between sectors. In short, mining, oil, and gas yield super high returns, financial institutions and infrastructure do pretty well, and manufacturing, agribusiness, and services are at the bottom of the pile.

Figure: Manufacturing is less profitable for the IFC than banking or mining

Source: Cole, Melecky, Mölders, and Reed (Management Science 2025)

Many development finance professionals would respond to everything I’ve written above: “yes, we’d love to lend to an export-oriented agro-processing sector in Malawi, or the manufacturing sector in Ethiopia. But there are no bankable opportunities there. We have an obligation to make money.”

My guess is that Taiwanese or Korean policymakers in the 1960s could’ve said something similar. The private sector didn’t want credit to build manufacturing export businesses. They wanted to buy banks, and build apartment buildings, and open retail import businesses. And when they did build manufacturing plants, they wanted tariff protection to produce import-competing goods for the domestic market.

This is where export discipline came in. Forward-looking policymakers did not surrender development strategy entirely to market signals: they restricted their subsidized credit to projects they felt were in the long-run developmental interest of their countries.

Fixes: bring back export discipline

The challenges facing the private-sector development finance industry aren’t new, but they’re increasingly urgent as finance swallows up more and more of the global development sector. Let me end by quoting from the list of policy recommendations from my friend Charles Kenny’s 2021 essay on how to get IFC back in the development game, which anticipates many of the arguments made above:

- “Shift the portfolio mix in [poorer] countries towards investment in tradeable manufacturing, services, agriculture and agro-processing, alongside infrastructure and services prioritized on their contribution to trade competitiveness and global value chain integration. [...]

- “Move further toward tolerance of failure by de-emphasizing returns as a project success measure and including incentives for groundbreaking deals in new sectors/ industries alongside development of metrics that encourage rapid exit from failing approaches or investments.

- “Use subsidies solely in the selective, competitive, support of investments proactively chosen based on potential impact on sectoral development outcomes.”

In short, Washington's new model of development finance needs export discipline. If subsidies for private investors are going to contribute to development, they need to target the industries that are going to drive growth and job creation. Sometimes that will be in tension with maximizing short-run financial returns. So be it. The whole point of public subsidies is to nudge the private sector to do things that are socially optimal even if the market doesn't sufficiently reward them.

There's nothing wrong with development finance helping investors make money. But it also needs to help poor countries make stuff.

--